Shelby Livingston | March 7, 2018

The nation’s largest health insurer, UnitedHealth Group, is following rival Anthem’s footsteps with a new payment policy aimed at reducing its emergency department claims costs.

Under the policy, rolled out nationwide March 1, UnitedHealth is reviewing and adjusting facility claims for the most severe and costly ED visits for patients enrolled in the company’s commercial and Medicare Advantage plans.

Hospitals that submit facility claims for ED visits with Level 4 or Level 5 evaluation and management codes—codes used for patients with complex, resource-intensive conditions—could see their claims adjusted downward or denied, depending on a hospital’s contract with the insurer, if UnitedHealth determines the claim didn’t justify a high-level code.

Minnetonka, Minn.-based UnitedHealth said the policy is meant to ensure accurate coding among providers. But hospitals fear the policy could squeeze reimbursement even further and lead to lower revenue.

UnitedHealth’s policy is different from Indianapolis-based Anthem’s, which has been denying coverage for ED visits that it decides were not emergencies after the fact. But both policies are aimed at lowering the insurers’ spending on ED claims. Taken together, the two insurers’ emergency department payment policies could represent a very real threat to providers’ bottom lines.

“Some hospitals are going to be hit financially, are going to be paid less, either through straight denials or through down-coding to a Level 3, and it is going to be a big hit for some hospitals on the ER revenue … unless they can truly justify they are providing the care or the services that’s really needed,” said Dr. Christopher Stanley, a director at consulting firm Navigant who worked for UnitedHealthcare for close to a decade, of UnitedHealthcare’s ED policy.

While Anthem’s program is meant to ensure low-acuity conditions aren’t handled in the ED, UnitedHealth’s policy is focused on making sure payment for emergency department claims coded for the highest-acuity patients is justified.

UnitedHealth will be using its subsidiary Optum’s tool, the EDC Analyzer, to audit facility claims submitted with Level 4 and 5 codes after a patient visits the ED and is sent home. The Optum tool takes into account the patient’s medical issue, co-morbidities and the diagnostic services performed during the ED visit to determine what UnitedHealth believes is the appropriate code.

Emergency department facility fees are coded on a scale of 1 to 5, reflecting the complexity of care delivered and the amount of resources devoted to the patient. Level 1 codes are for low-acuity conditions, while Level 4 and 5 codes are for the most serious conditions that require lots of hands-on treatment, such as blunt trauma or severe infections. Higher codes are more expensive for insurers.

UnitedHealth’s policy applies to all facilities, including free-standing emergency departments, that submit ED claims with Level 4 and 5 codes for members of the insurer’s commercial plans and Medicare Advantage plans. A December 2017 bulletin published by the insurance company also said the policy applied to members enrolled in Medicaid plans in some states, but that’s no longer the case for now. It’s important to note that the policy does not affect charges for professional services.

UnitedHealth recorded $201.2 billion in 2017 revenue and serves 49.5 million members. Its commercial enrollment totals 29.9 million people, while its Medicare Advantage enrollment is 4.4 million.

There are a few exceptions to the policy. It does not apply to claims for patients who end up being admitted to the hospital from the ED, critical-care patients, patients younger than 2 years old, or patients who died in the ED. The policy also excludes claims with certain diagnoses that often require greater than average resources when treated in the ED, such as significant nursing time, according to a UnitedHealthcare bulletin.

“The goal of this revised policy is to ensure accurate coding by hospitals, and ultimately promoting accurate coding of healthcare services is an important step in achieving the triple aim of better care, better health and lower overall cost,” a UnitedHealth spokesman explained.

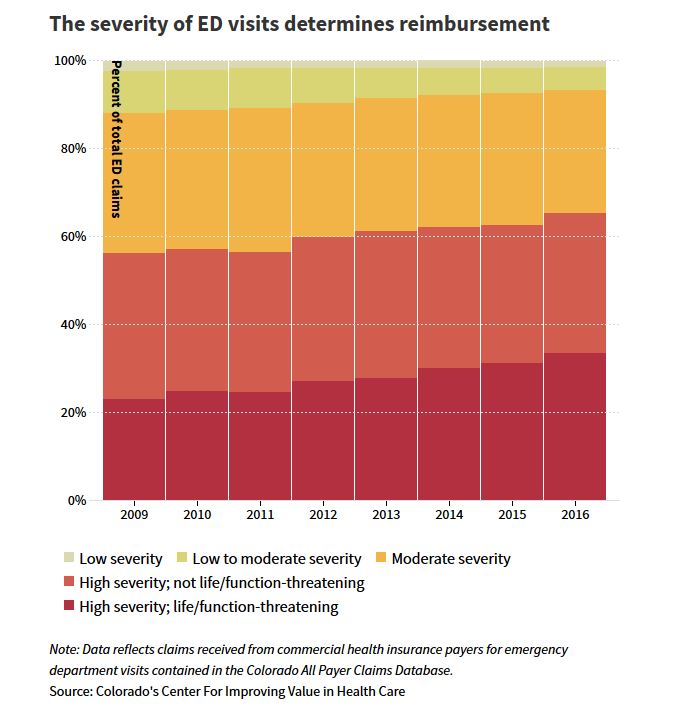

The policy came about because UnitedHealth said its claims data showed the frequency of claims with Level 4 and 5 severity codes has risen by more than 50% from 2007 to 2016, the UnitedHealth spokesman said. The company estimates that the more frequent use of those codes has increased U.S. healthcare costs by more than $1.5 billion, while also causing patients to spend hundreds more in medical bills.

The American Hospital Association held a webinar with UnitedHealth in late February to explain the new policy to AHA members. The AHA did not answer multiple requests for comment on the policy.

UnitedHealth expects only a small subset of hospitals to be affected by the policy, namely those facilities that have shown a lot of variation in what they assign the highest severity ED codes. For instance, one facility billed UnitedHealth $275 for a patient’s ED visit for a fever and assigned the visit a Level 2 code. Three years later, the same facility saw the same patient for another fever and coded the visit at a Level 4. The bill amounted to $1,200.

There is no national standard for hospitals to look to when coding ED visits. Instead, the CMS allows each hospital to set its own guidelines. Hospitals don’t like that UnitedHealth is imposing its own billing methodology on them.

While UnitedHealth said hospitals that experience claim adjustments or denials would be able to appeal the decision, providers argue that appealing the decision will be difficult and time-consuming because they don’t know the ins and outs of UnitedHealth’s proprietary algorithm for determining the appropriate code. For the same reason, they say they won’t know how to align their billing guidelines with UnitedHealth’s to ensure they aren’t downcoded.

“They’ve got this point system out there, but they’re not sharing what that point system is,” said Andrew Wheeler, vice president of finance at the Missouri Hospital Association. “So there’s no way for a hospital to duplicate what they’re suggesting the level of assignment should be.”

Hospitals worry that the policy will be yet another way for insurers to deny claims.

UnitedHealth said the claim adjustments won’t affect a patient’s cost-sharing, but providers argue that if a claim is denied outright, patients could be on the hook for the entire ED visit.

“It’ll just make it more difficult to collect for services, said Jim Haynes, chief operating officer at the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association.

Haynes said Arizona hospitals are already having difficulty getting bills paid for UnitedHealth plan members, and in some cases are seeing as many as 20% to 30% of claims submitted to UnitedHealth being denied, though not necessarily due to the new ED policy, he said.

Navigant’s Stanley, however, said the policy is a reasonable one to address increasing ED visits and the severity of the claims associated with those visits.

The number of ED visits per year has steadily climbed over time, reaching 141.4 million in 2014, up 8.4% from 130.4 million in 2013, the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows.

Meanwhile, the use of Level 5 codes has increased, leading to increased ED spending.

A 2012 report from HHS’ Office of the Inspector General shows the same trend for Medicare claims, finding that the use of Level 5 codes for ED visits increased 21% from 2001 to 2010, while the use of all other codes decreased.

There are downsides to the policy, Stanley said. Information included in a claim does not always tell the whole story. Not every service performed for a patient will show up in the diagnosis codes used. But overall, UnitedHealth has “done a very good job of trying to use data in a very rational and reasonable way in situations where there may be some potential upcoding,” he said.

Some experts argue the increased use of high-severity codes is not the result of upcoding, but is because patients with minor conditions are opting for urgent care and retail clinics instead of heading to the emergency department. “Patients who come to the ED are sicker,” said Laura Wooster, the associate executive director of public affairs at the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Employers and health insurers, including UnitedHealth, have long been using incentives to steer patients toward lower-cost settings when they need care. UnitedHealth has also been buying ambulatory care centers to that end. Its Optum unit bought Surgical Care Affiliates, an operator of ambulatory surgery centers, in January 2017.

Anthem’s ED program is another policy deterring patients with low-acuity conditions from seeking care at the ED. Already, hospitals say the claim denials resulting from Anthem’s policy are piling up and they are being forced to go through burdensome appeals processes.

The Missouri Hospital Association’s Wheeler worried that as Anthem’s policy keeps those patients with minor conditions out of the ED, that could make it look like hospitals are using Level 4 and Level 5 ED codes more frequently.

It “magnifies this issue on the UnitedHealthcare side,” he said. “The two policies may influence each other. I don’t know what that result will look like, but it’s something I’m going to be paying attention to and watching.”

Source: Modern Healthcare